essays.

poetry, meditation, and cultural investigation.

Celestial

“Celestial” is a poem written by artist Odón Nicolau. The passage relates to a sentiment of escape, faith, and reunion with the divine.

I ran away from the Babylon.

Sex, pills, and potions excite me no more.

I can’t find my place at the synagogue.

The holiest of saints, but still a sinner, lord.

Please show me the sky through this thunderstorm

I know there’s beauty in a thousand flaws.

The woman of my dreams is sleeping next door.

I send her vibrations of percussive love.

The future is nothing we seem to know.

Sunbath

“Sunbath” is a literary meditation written by artist Odón Nicolau. The passage in English reflects, through an appreciative narrative, the fundamental beauty of rising with the sun.

Refreshed by sunbathing under the early morning rays of abundance in the form of natural, never-ending sea tides.

I wish more of us came together to be illuminated by the yellow-hued blue sky that promises another radiant journey.

Together, we discover, learn, and evolve.

In fact, we’re in constant evolution, learning from the profundity of our earthly experiences.

Each day we get closer to the primal essence of our creator.

This way, life is born and our spirits wonder in nature.

Costumes

“Costumes” is a literary meditation written by artist Odón Nicolau. The passage in Portuguese briefly investigates the nature of our identity as decision-making beings.

Costumes e hábitos formam a identidade autêntica de cada um de nós.

Somos as nossas decisões e experiências manifestadas no espaço e tempo físico.

Esta experiência pode ser transformada através de estímulos concientes, ou através do universo.

Transformar a realidade requer uma visão, uma vontade extremamente conectada à consciência.

Por onde começa esta conexão?

Pela sensação de estar mais próximo, à algo inacreditável.

Uma incrível transformação.

Natural

“Natural” is a literary meditation written by artist Odón Nicolau. The passage in Portuguese reflects on the artist’s relationship to the naturalness of the sea.

Em frente ao mar, a minha existência parece complementar a expansão do universo.

A abundância das ondas é um sinal vital da constante renovação que passamos.

A beleza de respirar as brisas frias deste amor oceánico, aproximam-me ao criador e ajudam-me a começar mais uma manhã com a criatividade à flor da pele.

O nascer do sol ilumina a minha visão e alimenta a minha chama interior.

A pureza das pequenas rochas revela o equilíbrio natural.

Acredito que a vida será sempre abundante, e a força vital permanecerá renovável.

Trenes

“Trenes” is a literary meditation written by artist Odón Nicolau. The passage in Spanish briefly reflects on the value of time.

Las paradas del tren me parecen excesivas.

Pienso en reestructurarlas de modo a que hayan menos obstáculos para llegar a mí destino.

El tiempo es tremendamente valioso.

Aunque sea invisible y no lo veamos pasar por nuestras válvulas sanguíneas, se puede decir que el tiempo define la vida, y su contemporánea, la muerte.

Es impresionante cómo podemos cambiar nuestras vidas, cambiando la percepción y utilidad que asociamos al tiempo.

La mente se vuelve más serena al percibir el valioso cielo temporal bajo el que vivimos.

Amemos el tiempo.

Early African Art in Terracotta

The original artistic heritage of Africa might have begun with the fabulous terracotta objects made in the region of Nok.

Seated Terracotta Figure from a Middle Niger Civilisation. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

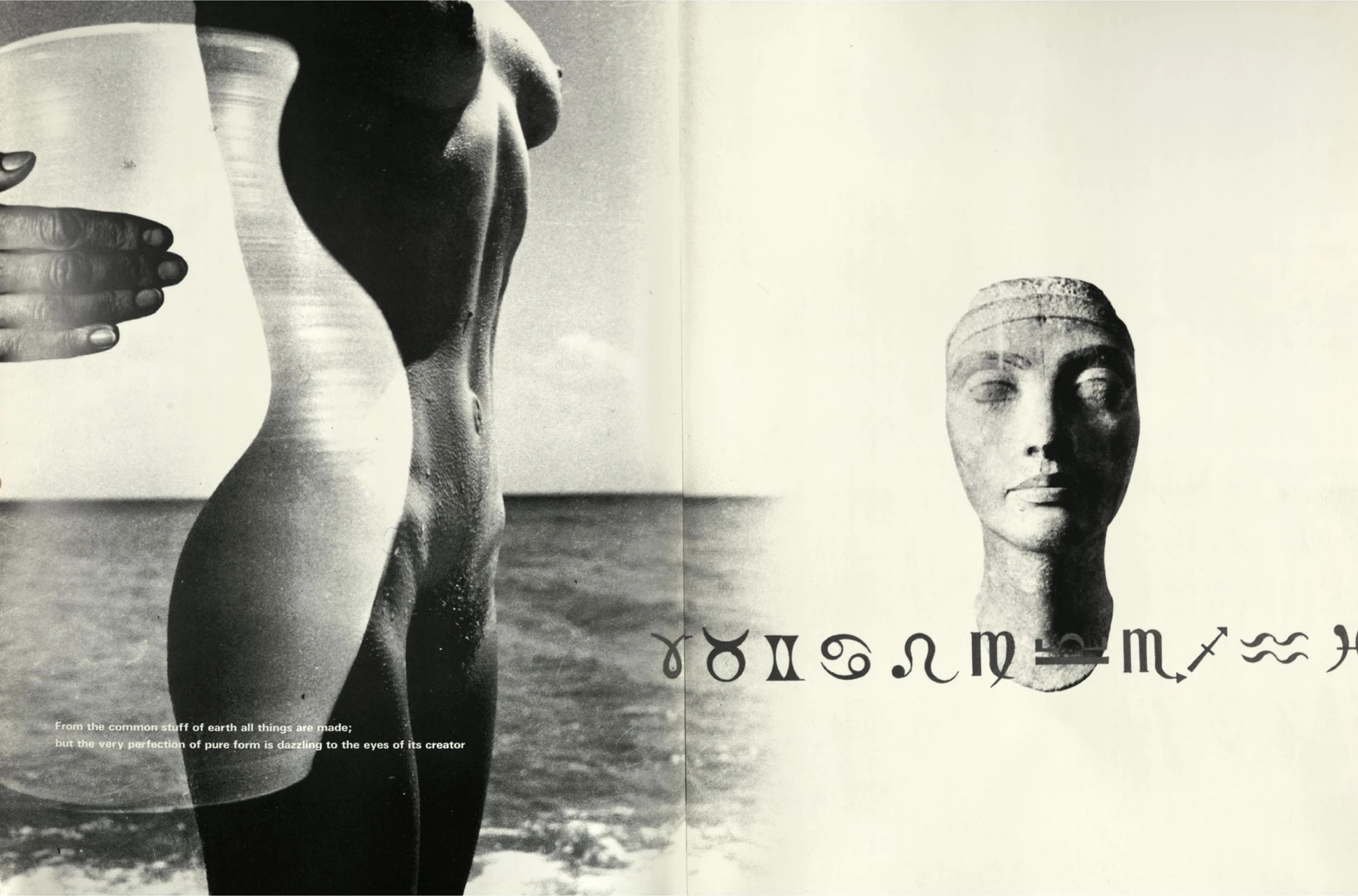

The early history of Africa is written in terracotta. Clay was once the chosen element employed to shape countless expressions, which are known to us today as the oldest forms of art in Africa.

The use of metals would incite the greed of the smelters who've melted and transformed it. The use of wood would inevitably fall under the pray of termites. Therefore, clay or terracotta, given its low value, was employed on various occasions.

Additionally, clay offered the advantage of being shaped directly by the hands of artists, without the need for extra equipment. As for its cooking, the technique of making pottery for daily use existed in Africa for millennia.

Some terracotta artworks would be left out to dry with the sunlight, while others would be boiled in the ashes of an open oven, at about 300ºC, or at even higher temperatures as a means for creating more resistant figures.

Memories of the Nok Region

As far as we know today, the terracotta figures found near the territory of the Nok, in central Nigeria, are one of the oldest, being dated according to thermoluminescence studies between 500 b. C. and 500 a. C.

Head of Jemaa from Terracotta, 500 b. C. National Museum Lagos.

The artists who worked in the territory of Nok used the same material for their sculpted figures as for their kitchen utensils, the timeless coarse-grained clay.

Some of these artworks could reach up to 1,20 meters, signaling a magistral dominance of the molding and open-air cooking techniques. Many of the sculpted figures are hollow, for which the artist had to sustain the same thickness throughout the figure and empty the parts that perhaps exploded while exposed to heat.

The technical competency, as well as the stylistic dominance, discerned in these artworks, motivates us to believe that the art proceeding from the Nok region represents the early unfolding of a vast artistic tradition in Africa.

In no form or shape does one observe discrepancies. This suggests that the art from the Nok region had an articulately defined identity.

Similar to the Head of Jemaa above, the pupils are often deeply pierced, as were the holes in the nose, the ears, and in instances, the mouth. The lips were well delineated, by an upper lip that closely reached the bottom of the nose. The expression of the whole was quite lively, all the more so since even the hairstyle was faithfully reproduced.

The taste for adornments among the groups inhabiting the region of Nok is indisputable. Some of the statuettes found, depicted small characters that literally crawled under the weight of necklaces and bracelets. Surprisingly, along with them have been found hundreds of quartz beads and other materials from which these adornments were made.

Elephant Head from Terracotta. Photographed by Dirk Bakker at the National Museum Lagos.

While most of the artworks closely resembled reality as far as their form goes, others appeared as if submitted to austere geometrical schemes, based on spheres, cylinders, and cones. The motive for these transformations remains unknown.

Either way, it cannot be due to incompetence, since the artworks of animal heads found in the Nok region demonstrate that the sculptors were capable of creating completely realistic depictions that evoke life.

The reason behind these contrasts could be hypothesized as respective to existing religious traditions in the region.

Some researchers believe that these stylistic variations were due to the fear carried by certain artists, of being accused of sorcery if they created totally realistic human figures. Similarly, others have stated that certain animals were reproduced with greater accuracy because they formed part of the traditional symbols of the community.

During the first millennia after the death of Christ, the art of Nok began to decline, nevertheless the tradition had its continuity. By observing the art of latter groups in the region, such as the Ifé, a group that has given the world some of the most beautiful and early creations of antique Africa, the Nok people contributions remain divine.

Intro to Antique African Art

Begin a discovery journey through the fascinating origin and meaning of antique African art to humanity.

African Mask from Gabon, photographed by Ninara

Writing about the antique arts of Africa awakes, inevitably, a delicate predicament of equilibrium between its ethnology and aesthetics, both being equally significant perspectives. Hence, a narrative that exclusively depicts the arts of Africa from an aesthetical perspective, restricts it from a large portion of its meaning to the people of Africa.

It's as if Christians in Europe, completely ignored the Bible and then attempted to fully appreciate the tympanum of a Roman cathedral. So equally, when dealing with the art of Africa, for us to truly appreciate its beauty, we must understand its motive, its purpose, and its mythical sense for the African artists and those who celebrated it.

Otherwise, we hold a beautiful, yet incomplete portrait of the African identity and culture.

Similar to the aesthetics, if a narrative on African art chooses to privilege its ethnological features over the aesthetics, it further mutilates the creative spirit, reducing it to the object level, and overlooking the fact that all artworks were purposefully made to serve the people.

The time has come to declare that the antique arts of Africa enrich the artistic heritage of humanity. These works not only remind us of the origin of our creative nature, but also deserve to be appreciated to the same extent as other masterpieces that, thus far, have savored much higher recognition such as the works of Michelangelo or Picasso.

It's time to better appreciate the beauty, the power, the delicacy, and the compelling nature of antique African art.

Couple Wooden Statue by a Dogon artist (Mali), from the 19th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The complete appreciation of African art encourages a conscious effort from the Western spectator to retire from a habitual manner of reasoning about art, and strive to adopt the vision of the artists who create it, and the people it served. This point is especially significant due to the most delicate conception of them all, the Western idea of art.

The notion of art for the Western spectator is extraneous to that of the traditional African culture.

This doesn't mean that the beauty of antique African art hasn't flourished in other parts of the world, even though it wasn't called art and carried a distinct purpose as that of Western art. To this, the spectator must ask him/herself:

What then, replaces the Western notion of art in the African culture?

In the spirit of the African people, the art which was well made or pleasing to the eye is based on moral principles, and that which was useful and well acclimated to its purpose was based on traditions.

It's important not to ignore that underneath the antique African artworks’ apparent aesthetical attraction, there was always a philosophical dimension. The antique African artist existed to support social life principles.

In Africa, several of the antique artworks were consecrated to the glorification of a reign or royal community. The strong influence of royalty in arts, had often signified the birth of a roundup of artworks deliberately created to venerate the ruling class.

Antique African art was greatly founded on spiritual and religious fundamentals. The king or ruler was often regarded as a being of divine essence. Hence, this form of art embodied a myriad of moral and social standards.

Through its motifs and symbolism for example, the art from Africa fostered social cohesion and allowed hierarchies to function, inspiring respect for the customary laws and repressing misconduct from the people.

Due to this particular social orientation of antique African art, the human figure has been the most portrayed expression. Animals were also represented as characters that recreate and express the human behavior in a wilder form.

Terracotta Sculpture, made by an Igbo female artist from the Igbo village of Osisa. The British Museum.

The African artist often had to respond to orders originating from supreme entities, such as court officials and secret societies. His inspiration didn't arise from an individual ambition, instead, the artist performed within the traditional norms, which always allowed space for a diverse set of artistic creations.

Since a superficial glance can provoke the spectator to assume a uniform art characterized by specific immutable traits, it's crucial to recognize the great geographical influence on the antique African art panorama.

Each region of Africa has created its art forms which derived uniquely from the visible manifestations in the collective psyche of its ethnicities and royals.

In each ethnic group of Africa, art was manifested in all aspects of life and went beyond the traditional domain of statues and masks, to englobe adorned and carved objects, musical instruments, weapons, and finally, corporal arts such as headdresses and scarifications.

The arts of each ethnicity were the expression of a particular manner of seeing the world, built upon tacit, unconscious, and spontaneous experiences that orient the creation of vivid, comprehensive, and appreciative or fearful realities for all its members.